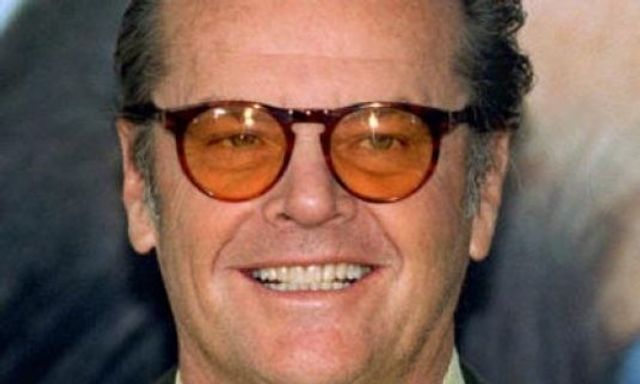

Jack Nicholson and I first met at Roger Corman’s office sometime in 1966 or 1967. We’ve remained friends since then. This conversation was tape recorded in Nicholson’s living room in the Mulholland Drive house he’s lived in for about forty years, on August 11th and August 22nd, with a follow - up final phone conversation on September 11, 2006. The following has been edited for clarity.

Peter Bogdanovichs: I feel I haven’t sat down with you in thirty years.

Jack Nicholson: Well, we haven’t sat down in a while. We’ve had a lot of talks, though, brief, but they always retained serious content.

You’re looking good, Jack.

I’m feeling pretty good. I’m feeling the old Pickford-Fairbanks... Am I too old to be in movies? I’m feeling that part of it. That’s what I feel about longevity.

So when did you first think you were going to get involved in writing or directing or acting in movies?

You know, I came to California at 16, out of school, kind of thinking I would go back to college after taking a half a semester off. I come from a non - affluent background - no help, no connections - so therefore I was a typical teenager wondering what in the name of God am I going to do to make my way in life. I wasn’t clear enough, being an adolescent, to know that I sort of always hoped to do this, as people who love the movies do, anyway.

You did - you mean, even when you were much younger?

Yeah, I was an assistant manager of a theater in my home town, the Rivoli in Belmar.

A movie theater.

Yeah. And always loved the movies. So when I got my job at MGM, the front part of my head was saying a very honest thing. I wanted to see movie stars, ‘cause I’m a big fan. I was ready to go back - I actually had my ticket-I bought it on my birthday. I didn’t get this job that I applied for at MGM first time around.

What year was this?

This was 1955. In fact, I got my job in the movies through the only door that wasn’t inside a studio wall in all of Hollywood. Labor Relations at MGM - you know how you walk by the gate there, and then turn and go into the Thalberg building. Well, over that spiked gate was this one door - didn’t even have a step - Labor Relations. That’s where I applied and that’s where I started in Hollywood. I was an office pinkie in the cartoon department.

I read somewhere that you grew up thinking that your grandmother was your mother, and that your real mother was your sister.

Yes, she was also a dancer in show business. She was an easy novel to write the story of my sister/mother’s life. But I didn’t find that out until way into my 30s and they had both passed on. By then, I was a supposed introspective artist. I understood it - I know exactly what my initial reaction was-gratitude.

Really?

Absolutely. Well, you know, you get it in a moment. It’s a real moment. And I am that kind of person-what do I feel-and had the tools to know what I feel. Gratitude. I’ve often said about them: Show me any women today who could keep a secret, confidence, or an intimacy to that degree, you got my kind of gal.

Didn’t that information overwhelm you in some way?

Well, it definitely overwhelmed you. It got my attention.

To think about it?

That was the first thought. I had many other thoughts. One of the toughest ones about being grateful was: I didn’t have to deal with it with them. They were dead. You don’t like to admit you’re happy in any way that two of the people you loved the most in your entire life had passed on. But that was one of the reactions. Look, it’s why I can’t be my normally liberal self totally pro-abortion. In today’s world, I wouldn’t exist - you understand what I mean?

You mean you would have been aborted?

Yes. June [his mother] was only 16 - she was having a good career herself - chances are... You know, it’s one of those things you think you’ll never change your mind on in life and I changed my mind on it - not for logic, but for karma.

Did you ever know your father?

No.

Do you know who he was?

I’m pretty sure he’s deceased, but within the family unit it is still a somewhat open discussion. But not that open. A pretty good guy - I talked to him - when I found this out on the phone. But I didn’t want to get to know him. I didn’t have the urge - to see what this is all about. In my 30s, psychologically I’m formed. No, I didn’t see any real reason for it. And there were plenty of reasons to go into it.

Not to talk to your dad?

To re-include this - what’s normally a cardinal relationship in your life - under those circumstances.

Did knowledge of the truth make you have to reexamine your childhood? Go back and rethink it?

Well, it did clarify a lot of things, because in either event my grandmother was a single parent. So somewhere in there you start thinking about everything - I always thought it was interesting that my supposed parents’ relationship broke up kind of congruent with my birth, and as deep as an 11- to 14-year-old mind can go, I thought, »I wonder if there’s something... This seems strange to me.« It verified certain very murmuring intuitions. I didn’t invest in it. It wasn’t like, »Oh, this might have happened.« It was just that it had gone through my mind. Other things it clarified: the nature of my sister/mother and my grandmother’s relationship. They were Irish warriors and powerful women. This is ideal. I had a father-figure, Shorty Smith, still one of the greatest people that ever lived in my opinion.

Who was he?

He was my other sister’s husband.

Not the sister who was your mother?

Not that sister.

There’s another sister.

June and Lorraine. Incidentally, I found this out through Buck’s friend when they did that Time cover on me.

Buck Henry?

Yeah. His girlfriend was an editor at Time and they got the information.

It must have blown your mind.

It definitely blew my mind. First of all, I call home and Shorty was there. And I said, »Shorty, I just got this call - and so on.« He says, »Absolutely not true.« I said, »Okay, Shorty, good, I didn’t think so.« Now, about 2:00 o’clock their time, so they must have burned some oil on this one, the phone rings and I say, »Hello.« And he says, »Jack, it’s Shorty, I’m gonna put Lorraine on the phone. I just want to say one thing - she’s been crying all night. Here she is.« That’s the way he led into it. And then the discussion ensued. And that’s when I thought, »Geez, this is mind blowing, but I’m glad I didn’t have to deal with it all those years.«

You didn’t have to deal with the two people...?

With all the people. In a way, I’m raised by women, grew up in a beauty parlor, had a very strong Polish railroad brakeman, honest guy who was - he had acknowledged when I was 8 or 10 or in there that I might very well be a lot smarter than he was so I didn’t have a repressive, competitive father. I always have a plan, it never goes that way but normally it goes better than my plan. I didn’t have the conflict with the father figure, but I had the strength of the father figure. I didn’t have a possessive mother figure, I had a committee unbeknownst to me who obviously were thoughtful and committed. One of the things I’ve been lucky about in life is I’m not subject to emotional blackmail, which is normally one of the big spins you get from your family. So this was just, by structure, not happening. So I looked at it as ideal. And all the concern, I mean extra concern.

When did your grandmother and mother pass away? Had you already become successful?

When this came out through Time, they said, »We’ve heard this rumor, Jack.« And I said, »It’s true. But, you know, I’m an open honest guy - I would prefer you didn’t write about this. Write about it if you want to, but the reason I don’t want you to write about it is I’m a writer. And I’ve never had anything this dramatic to write about in my life and I may want to write about it.« And, interestingly, to the credit of the fourth estate, they didn’t. I was asked about it a dozen times. And not one of those people felt the need to write about it. It’s why at this moment I sort of stopped the flow because there’s certain things about it that needn’t be discussed, and that I still may want to draw on myself, from a literary point of view. Like when they died. That’s why »My Sister/Mother June« is an easy novel.

Yes, it’s an extraordinary story.

She went from being with [Broadway impresario] Earl Carroll, went south with him, hung out with the Lucky Luciano ambiance of Miami. The war broke out, she became the girl in the control tower at Willow Run, which was the busiest Air Force position in World War II and from that married America’s leading test pilot, one of the men who actually was one of the first men to break the sound barrier before it was done officially. One of the first people to fly in a jet plane, a ne’er-do-well, son of a Connecticut brain surgeon, with a drinking problem. Her life was so specific... I had never done a major studio picture. She was terminal. We were on the outs. She had fears for my future - she was my sister. And she’s here and with terminal cancer, and I knew I would be the only person who could deal with that. I’ve got a pregnant wife, I get this crazy picture with Josh Logan [Ensign Pulver., 1964], for the money, basically. I desperately needed money.

I had to say goodbye to her - going on location - told her everything I thought about death. And told her everything: What I thought about death and where it was and so forth. At the end of the discussion, because I was going down to Mexico, she looked me in the eye as I was leaving and said to me, »Shall I wait?« And I said, »No.« After I said »No«, I went into the elevator and collapsed, of course. All of us flew down to Mexico - we got held over a day because of a thunderstorm - and almost immediately after I arrived, I got the wire she had passed away. It’s so wildly dramatic, you know, it’s a strange thing. As I say, it’s the easiest novel. I collect people who are easy novels.

It’s an amazing story.

When I got back from that picture my daughter Jennifer was born - the day I got back.

You were still a kid then.

Yeah. Twenty-seven.

When we first knew each other I felt that your primary interest was writing and directing, more than acting.

That was because I wouldn’t have planned to be working for 10-12 years and studying, working along, not making a good living, but surviving with a family, and a child and take twelve years before suddenly overnight - I had the experience - wait a minute - I’m a movie star! I’ve got to change my plans.

That was after Easy Rider. [1969].

One screening in Cannes. I know that audience, I know exactly what it is - I’ve been there, done that. I don’t think anybody ever experienced that apocryphal story of »My God, I’m a movie star« with as much background to be sure that it’s true. Great. I had 10-12 years. It’s a very demanding form of filmmaking and most of the lessons are what I still follow - it’s why I’m kind of a no-nonsense movie-maker. There was no nonsense in those days with Roger. Price - time - that’s it. Other than that, he didn’t want to hear from you. Very exacting formula.

Right. And you steal and cheat and run and grab it and make it, no matter what.

Develop things, learn how to adjust. You don’t realize you just can’t dig in, you have to let things go, keep rolling, keep rolling.

When we did the two westerns [Ride in the Whirlwind [1965] and The Shooting [1967], directed by Monte Hellman, Nicholson played the lead role in both], I was Monty’s assistant - he wouldn’t let me cut nothing. All I did was learn how to do trims, and stock them, and code them, and so forth - like an assistant. I did that picture [Head, starring The Monkees, directed by Bob Rafelson].

Didn’t you write that?

I wrote that, yeah, with Bob. But even before that [producer] Bert [Schneider], in his wisdom, kind of got my feet wet in the editing room, which was one of the biggest acting lessons any actor will ever get. When you go into an editing room you learn a lot about acting, not just editing. I thought I knew quite a bit at that point. But I’d given up acting, for the most part. As you said, I was going to be a writer - I’d written a lot - I had a commitment to direct a picture at BBS, and I was part of that great period of the American underground film movement - a very far-out, theoretical movie-maker. And that’s what I thought I’d like to do. I was being honest - 10-12 years as an actor. Everybody always said I was good, but that’s worse than if you’re a total unknown. It’s just: »well, nothing’s happening for the guy« - whatever that crazy in-town thing is. Fortunately, I did not know or I would’ve been more depressed than I was.

I remember how furious I was: I sat up with [Henry] Jaglom up at the Old World ice cream parlor at a table - there were 5 or 6 of us actors; like we were there every day - and they had all had an interview for The Graduate. [Mike Nichols, 1968], and I couldn’t get an interview. After my first interview with Solly Viano, which concluded with the following statement: »Well, Jack, you seem good,« he says, »very unusual. Frankly, I don’t know what we’d need ya for, but if we need ya, we’ll need ya bad.« You have a very different image of who you are in the face of that kind of rejection. I didn’t think I was all that strange.

But wasn’t the part in Easy Rider. [1969] kind of an afterthought?

I was to oversee the production. I had co-produced - by then, they kind of knew who I was at BBS. Dennis [Hopper] and Peter [Fonda] had gone to New Orleans, gone mad - I shouldn’t say too much about that out of school. But gone mad - and Bob [Rafelson] wanted me to play the part more than I knew they wanted me to play the part. I knew [cinematographer] Laszlo Kovacs, I knew all the people who worked non-union pictures, and they [the producers] wanted me to just go down, »Be there and make sure that you and the rest of your dope-fiend friends don’t go crazy. Keep them on a semi-even keel. See if you can bring this picture in - keep ‘em from killing one another - whatever they’re going to do.«

You were the responsible one.

Yeah, the company man. I’d written - Dennis thought of me as one of the best screenwriters in Hollywood at that point. I’d written something for both him and Fonda. They both liked me. They both trusted me. And they should. That’s why it worked out so well. Bert gave me the part - I read it - he said, »Can you play this part?« I said, »Well, Bert, in all honesty, a moron can play this part. This is a good part.« That was all of the discussion about the part. The rest was all about production and what’s going on and getting some people in there, replace some of the crew for him and so forth. And then I saw the early cut, and Bert said: »What did you think of your part?« I Said, »Well, of course, it’s great, very good.« I paused, »I could cut it better.« He said, »Well, go ahead. Cut it.« Which I did. Dennis trusted me, through the action of making the picture. And nobody at BBS would do anything that the filmmaker didn’t want him to do. It was the freest, best independent moment any of us ever had. It was totally perfect. And totally successful, we might add.

That never happened again, that kind of thing.

No, and it was because of the strange nature of Bert and Bob and Steve’s [Blauner] - old and lasting relationship. Bert was very, very important. He was benevolent. I mean, Bert is one of those guys: there’s nobody I would rather see running a studio he didn’t over-talk. He gave me a couple of cuts in Easy Ride., didn’t give me 90. Didn’t go around saying, »I’m the one who said - ,« you know what I mean, he didn’t have all that sickness. And he loved movie-makers. And because Bob - when they’d have a fast meeting - he’d let Bert handle it. So the dynamic was perfect for us.

It was great.

It was genuine.

How is Bob? Do you speak to him?

Yeah, he’s up in Aspen, he’s raising his new family. He’s got a few million wrist problems, but he’s Curly Bob, he’s fabulous.

I particularly liked that last picture you did with him, Blood and Wine., which for some reason didn’t get much attention.

Bob - because we started as collaborative writers - he’s the exception to the directing rule. With him I’ll argue like a fishwife - we don’t have that separation. We always had the same arguments. Blood and Wine., the arguments were simple, and the onward discussion was simple. Jennifer Lopez was going to be famous for her ass. When Bob overslept, we staged the short dance number in the picture - I did the rip-off of »Rock Dreams« - with my hands on her ass in an insert. He wouldn’t put it in the picture. I said, »Bob, you’re insane.«

Why’d he take it out?

That was the first five years of the discussion. Which then transformed into: The studio made him take it out. I said, »Isn’t this a little late to tell me?« Now, another few years go by, and not only didn’t the studio take ‘em out, his new argument is: »You’re crazy, it’s in the picture.« Fortunately, it came on TV; I looked - it’s not in the picture.

It’s the same thing we were talking about before: You’ve got to know when something in limbo is commercial. This is worth it’s time and the number of sprocket holes on the film in every sense of the word. First of all, I’m furious. »Why are you sleeping late and I’m having to stage this fucking dance number?« These kind of discussions which we’ve always had and loved, you know - we love each other. The other one was: »Bob, the form of this movie is a simple one - why we all liked this script: There’s no rooting interest. Everybody’s bad in the picture. There’s no good people in the picture. You can’t now put in one of your nimbly get-the-audience-to-like-somebody speeches for Jennifer Lopez, where she’s talking about being a Cuban boat-person.« You know, it’s just bad. And I never would win these arguments with Bob. He always thought he had some way of making the audience like something. And he correctly said, »You don’t want anybody to like you for anything. You’re just a hard-ass pain in the ass - you always have been - you always will be.« It’s in, it’s out. He’s the director. And my boss, incidentally, from the early parts of the story. I didn’t want to do Postman Always Rings Twice . [1981], directed by Rafelson] as a picture in the cold.

In the cold?

Yeah, as a cold picture - I wanted to do it in summer. Incidentally, he may have been right. Because that’s a really fine picture he made there. I never made James Cain’s book - and it’s a story that’s been ripped off a million times. The center of that book is they fuck on the [dead] body. Well, Hollywood ain’t gonna: They certainly - even the wildest of them - ain’t gonna deal with this.

That’s what it was about.

I felt, and he agreed, no nudity in the picture. Now, at that time, nudity was all over the place. »No, let’s do this most sexual picture without nudity. One shot of my bare ass laying on a bed like a baby picture - the exact opposite - that’s it.« Of course, Bob, covering all bases, we get to these erotic scenes and he’d be with a handheld trying to get a shot of a breast. I have enough technique to block two handheld cameras while I’m supposedly acting. I don’t know why I digressed into that. But it’s so different. Another one that’s interesting, Man Trouble. [1992; Rafelson]: Look, I know from Marshall McCluhan, when you break a cliché you release hybrid energy in communication. Stanley Kubrick said to me one day, »Every scene has been done. Our job is, do it a little better.«

With Bob, on Postman., »Look, in these sex scenes, we’re no nudity and we’re in ‘40s pants - I always wonder how they go from that kiss to suddenly they’re entering someone. How did this happen? Let’s have a cut in these ‘40s pants of me with a big railer on, no nudity, just the bulging pants.« I get me a dildo, made all the preparations and we get to the scene, he thought I was kidding. The immediate dildos didn’t work, they couldn’t rig it up right, so: »Go on upstairs on the set and get a boner, and we’ll - « So I find myself whipping my pudding trying not to have the set creek with an entire movie company listening. So, needless to say, this we didn’t do in that picture. But on Man Trouble., a place where it may not be as appropriate, I’m in the scene with [Ellen] Barkin and I’ve got the dildo this time, various sizes, and I say to Bob, »Now we’re gonna do this.« And he said, »All right, goddamit, you’ve been driving me nuts, we’ll do this shot.« And we do it, »Now don’t you fucking cut this thing out. I’ll kill everybody involved.« He leaves it in. Later, to my friends at a screening as they file out, I ask - and it’s huge on the screen - »What do you think of the codpiece-shot in it?« Not one person saw it - not one. I was stunned. I was surprised that nobody noticed the fuckin’ thing. Another lesson in film making.

Going back to the early years: Where did you grow up?

In New Jersey. On the shore. Neptune City, Spring Lake. Manasquana high school. Life guard, beach boy. Came to California, didn’t change much, they didn’t have the freeway. Lived out by the track. Went to the pool hall. I drove to the South Bay beaches, no freeways over there. The airport was in a different place. It was about the same amount of time it took me to get to the beach in Jersey.

So you felt comfortable here.

Totally. At that point I’m not thinking Hollywood, I’m thinking, »What am I gonna do?«

Why did you come here?

From the pressure of »Shall I go to college?« I’ve had a job from the time I was 11 years old on. And I always thought I was a fuck-off and lazy. I suddenly thought, »I don’t want to go to college where I really want to learn something and be insanely having to work all night at the same time. I’m going to think about this.« So June was here, and I thought I’d come out, look around California - interesting, and go back maybe Christmas time or skip a semester - and then go back to school. I had bought a ticket on my birthday to go back - you know, I was depressed - I thought, »Well, nothing’s happening much here, I better go back there and get serious,« and while I was down buying the ticket I got the job at MGM.

In the cartoon department.

Yeah. And I started - I remember this - fifth day of May (fifth month), 1955, which was my lucky number, too. Fred Quimby opened the MGM cartoon department on my actual birthday, and I went to work the week he retired. They closed the MGM cartoon department while I worked there and I was the last employee.

That’s strange, isn’t it - does that happen to you a lot?

Well, you hear it in every story.

Fate.

Yeah. Something that I didn’t particularly believe in. I’m too nervous a person.

You’re too nervous to believe in fate? That’s funny.

If I believed in fate, it means I’m lazy.

Why do you say you’re lazy, though?

I have no idea. I’ve been working.

You never stopped.

And I just like fun - I’ve had a lot of fun. I didn’t know for most of my life that that was good too, that you could work and have fun. I thought you had to be grim. You don’t know. I mean, let’s be honest, I’ve always been a confident person in a certain way, within reason. But we don’t know what we can do. I didn’t learn much about filmmaking in the two years I worked there. I mainly did look at movie stars. Stuff sunk in, I knew about the things that related to my job, production things and all that.

But you were there at MGM during the last few years of the old Studio Star System.

I saw everybody working. I was on those sound stages a lot. And decisions they’d make - [studio head] Dory Schary wouldn’t let any television come near the MGM lot. He was the last of them - and that’s why Universal shot up. Cameramen had in their contracts - not that they couldn’t watch television - they couldn’t own a television set. And, of course, television wound up saving them. But, you know, I saw everybody. Monroe, Bogie, Hepburn, Brando, Spencer Tracy, everybody worked there in the years I was there - it was hog heaven for me.

You were a big movie fan?

Oh, huge. And a weird one, too. I laid out on the lawn one day to try and get a look at Lana Turner’s underpants.

Did it work?

Well, not quite underpants, she was getting in a wagon - I got some leg in there.

Was that an interesting period for you?

Oh, totally fascinating. Watching the pictures, hearing the stories old George Godfrey told to me on the tram, he knew every story in the history of MGM. Judy Garland, Mickey Rooney, scandals, every story there was on that lot.

What was your actual job?

I did a lot of things. I prepared the paper for the cartoonists and kept -

You were in the cartoon department for the whole time you were at Metro?

Yeah. In fact, I might still be there if they hadn’t closed the place up. Well, this story I have told a million times - how I got started as an actor: [Producer] Joe Pasternak was sort of wild - and I talked to him a lot - he did all those musicals there. One day, in the elevator, he said, »Did you ever think about being an actor, kid?« And I said, »No.« Of course I had, a little bit, but I said no. So I go back, and my boss [cartoonist] Bill Hannah calls me up at the office, he says, »Jack, did you talk to Joe Pasternak in the elevator?« I said, »Yeah.« He said, »Did he ask you if you wanted to be an actor?« I said, »Yeah.« He said, »What did you tell him?« I said, I said no. He said, »Well, what the fuck do you want to be - an office boy all your fuckin’ life?« So they hooked up with the Talent Department and I read my first scene with them. This is how little I knew: when they said, Take this scene and we’ll have you read the scene, I thought it was about reading. I took it home, threw it on the top of my bureau and didn’t even look at it for the next week and a half. I ran into the messenger room, when they told me what a reading was I grabbed Ilona - she was a messenger girl - we read the scene together.

Amazing. And that’s how you started acting?

Yeah. They sent me to the Players Ring Theater for seasoning. It was the only theater functioning in L.A. Other than road companies, just The Players Ring and the Players. That was another great experience.

What did you do there?

I’m back to where I started - I managed the theater. And went to classes. Joe Flynn, the actor (McHale’s Navy. and many other things), was teaching the class the first night I went. I sit there and he talks to me. He looks at me and he says, »Look, this is the end of this session, and I don’t know how much I can teach an actor anyway.« I said, »Huh?« He says, »I do the best I can. But I’m gonna tell you one thing, everybody that you run into in this business is gonna try and get you to take voice lessons and change your voice. Don’t do it. That’s all I got to say.« That’s the first thing I ever heard in an acting class! »Don’t do it.« And, of course, all movie stars are made by their voices.

You mean like Bogart or Jimmy Stewart or Gable or Wayne...

I took the first lesson, no voice lesson. And I believed him. It’s the first thing I heard, why not? He’s a known actor, I’m not.

Smart piece of advice.

Great to get it as the first and only thing. Where did this perception come from? I know I have an unusual voice - it has smoothed out a little over the years, but I didn’t know then.

It’s something you don’t think of, really. But it is a fact. And you can’t grow it. It’s your voice.

That was the first and only piece of advice you got in acting, period?

That was it. Now, at that time - there was not much television in L.A. - so all the great character actors and people who weren’t movie stars or constantly employed in the movies, all wanted to work at these theaters. And they always auditioned for two plays - you know, one at each theater at the same time, so maybe not everybody, but a good slice of the working professional actors of Hollywood at that time would come down to these auditions. And I watched them read [audition], right? For three weeks. And I sat there and all I could think was, »None of these sonsabitches can read. I can’t be that bad.« I knew they were good actors, it wasn’t that I thought they were horrible. Because, you know, if you see Percy Shelton or whoever it may be, Robert Horton, Robert Vaughn - you know they’re good, but reading’s tough. And you know at that time I didn’t have any [method acting] experience so I’m expecting ‘em to give a performance. And I’m thinking, »Jesus Christ, I might have a shot in here.« So those were the first two things I learned.

Then how did you get a gig?

Well, the MGM guys - my first job - they had Matinee Theater. here. And they needed so many actors because they did a 90-minute drama every day. You went to work 2:30 in the morning, did a dress rehearsal -

Television?

Yeah. Live television - Matinee Theater. It was just starting. They built that whole NBC complex out there over this particular show. And that’s where television got started. Things like Playhouse 90., they were all shot in New York. There was some here. You know, I love L.A., I’m deep with L.A., I’m so crazy about it and its history. Remember, I don’t even know anybody, Peter. I worked around the theater and I asked Judson Taylor about classes, and he said, »One of the best is Jeff Corey. He doesn’t take everybody.« He set up an interview. I knew my contemporaries at the Players Ring, and the office girls, but it is a mysterious business from the outside. What the hell is it all about? I got serious once I started studying with Jeff.

When I got my first part at the theater, I had two lines in Tea and Sympathy.. One friend of mine who wanted to be an opera singer watched every night because I so over-prepared. Every single night I got a laugh with these two lines. And nobody ever really understood why, including me. I have to think I was so over-cranked, coming in with the line - »Who wants to go mountain-climbing in the rain?« They went hysterical on every night. I got used to it, but I think it was because I was so new and raw, and I came in carrying that 500 extra pounds of acting so when that line came out, the audience always laughed.

Did that do something to you, getting the laugh?

When you are an honest hick, you tend to be overly cool. You tend to pretend you’re not a hick - I never even stayed for a curtain call - I went home - I was working in the daytime, too, at MGM. Jeff recommended me for one of Roger’s pictures. The first time I’d had an outside reading for anything. And I went so crazy, I got that part easy - I think immediately. That’s it - I got the lead in a picture, my first read, The Cry Baby Killer. [1958].

Roger [Corman] directed it?

No. He just financed it. Kind of a hostage-teenage picture. I was so over the top at the reading, and screaming - they made fun of me - but I got this part. And I thought, »That’s it. Movie star. What’s so tough?« Well, the picture didn’t even come out for eighteen months. We won’t discuss how good or bad I was, we’ll let the chips fall where they may. Plus, by then they convinced me I was also weird-looking.

Really?

Well, one casting agent started off with this: »We don’t know what we could use you for, but if we need ya, we’ll need ya bad.« I kinda staggered out of there with my ‘50s crewcut, thinking I was a Dartmouth man.

So what happened after that picture?

Nothing. Needless to say I was not a movie-star, that’s for sure. In fact, weirdly, they had the world premiere, eighteen months later, across the street from the poolhall I hung out at in Inglewood when I first got there. My mother had to hit somebody with her purse who was heckling me on the screen - it was so humiliating.

Your mother or your grandmother?

My grandmother.

She got pissed off.

Well, there was talking in the audience. »Shut up!« I don’t know if she actually hit him with her purse, but she protected me. When I did Little Shop of Horrors . [1960], I knew it was a comedy.

You did know.

You couldn’t not know - the weird voice and all that. But, when we went to the premiere of that, when my scenes were on, the audience went insane. I’d never had much of a positive reaction from a Roger picture. I had a hot date with me - when they roared with laughter, I went bright crimson red, I was so embarrassed. I didn’t know how - you think you know, but you don’t know anything. I was like crimson red sitting in the audience because they were laughing. I’m sitting there thinking, »Oh, God, man...« I didn’t think it was horrible because somewhere I know it’s a comedy but I was still embarrassed.

Didn’t Roger shoot that in two days?

Yeah. That’s why he shot it. »I want to prove that I can make a feature-length movie - « (in those days they did a half-hour television show in three days shooting) » - in less time than they make a half-hour television show.« And it was wild. First of all, for the audition Roger didn’t want to open the gates at the Chaplin studio because then he’d have to pay. So [John] Shaner and I come down to Chaplin, we had to climb over the fence to get in.

Come on.

Oh, no. Absolutely. That’s only the beginning. We now go in to read the scenes for Roger in the dentist’s office. John is the dead body - his scenes are before - and then I come in. We read the scenes, Roger said, »Gee, I didn’t know you could do that - fine.« »All right, you guys, you’ve got these parts.« »Really?« »Yeah«,he said, »Now -« and he took the script - John’s part was on six and a half pages and mine was on five and a half. He gave John six, tore that one page in half, gave John his six and a half, gave me the other half - this is the epitome of how tight Roger played it. In my scene, while he was pulling my teeth, we’re shooting, and Jonathan Haze bumps into the dental machine which Roger had borrowed from his dentist and the thing starts teetering. (You know, everything was one take. And there was a little more to the scene.) The thing is teetering - Roger leapt into the shot and never even said cut. He just grabbed that dental machine and said, »Next set.« Oh, they were desperate days.

Desperate?

Oh, yeah. You know, Roger wanted me to write the first bike picture, Wild Angels. [1966]. Because by now he knew I also could write.

When was that?

I guess we must have already done the Westerns for him. Which is another Roger story. You know how Roger was: »Just give me two sentences...« We went in and sold him two regular B-Westerns. The one I wrote we called Ride in the Whirlwind. [1965], we kind of sold as an Attack at Apache Junction. or something, with a lot of stagecoaches and Indians. And the picture Carole Eastman wrote, The Shooting . [1967] we sold as an African Queen. in the desert. Now we go off, we write two art movies. All that underground movement is going on then. They had movie revivals up at the Lido, they had Greta Garbo. I’d never seen a Greta Garbo picture. I’d never seen a W.C. Fields picture. We started a film society Monte B & The Guys down at the Unicorn coffee house. We’d show Sasha Guitry and Zero for Conduct. [1933]. Monty was a film student at Stanford and knew about this stuff. But you didn’t ordinarily see these pictures. And then right after we did this film society, the greatest period for a movie-goer in history hits America. Do you realize that from 1960-something into the ‘70s, we expected to see a masterpiece every week and we did?

All those films from Europe.

Toho [Japan’s biggest production co.] had its own theater. We don’t get the European movie, or any of that anymore. It’s a big loss, I think. Sure, they may even figure out a way to make money on it, but not enough to penetrate what’s now a conglomerated situation.

No, all that’s gone.

But what a great break. Imagine, I’d seen none of it. Nobody’d seen the foreign films, really. So what with all that going on, we now bring Roger these two very classy Westerns. They’re not like everybody’s shooting people every two seconds.

They were art-house Westerns.

Yeah. I took them to Cannes - that’s the first time I went there. They didn’t know me, but Godard befriended me the first night - he came to the first screening and after that I was a »member of the delegation« of Cahiers du Cinema. - I went to film festivals with them. I got on really well with Jean-Luc, who doesn’t get on with many people. I was probably this American infant terrible, you know, I don’t think he was fascinated with my intellect, but whatever it was we did get along. He made me laugh. So I was sort of a local star almost. I never had any of that around here - and it didn’t add up to anything here. What - am I going to work in Paris? I don’t think so - I got enough problems in L.A. We brought them in to Roger - he reads the scripts with that look on his face. »Well, you guys, you ran a number on me.« We said, »What do you mean?« »You know what I mean.« I said, »Yeah, okay.« He said, »But you gotta go ahead and make the pictures.« Oh, good. »Why?« I said. »I’ll tell you why. Because with the deal I got, you make them for the price we’ve agreed to, I can’t lose as much as I’ve already paid you to write the scripts. So I may hate them, but I don’t want to lose money.« We wrote them, produced them, starred in them, directed them, edited them - all that. Monty and I made two color westerns on location with pretty good casts, for $85,000 apiece, which was what he gave us - we had to make ‘em for that. Well, we went a little bit over so that Monty and I - , for all that work - made $l400 apiece for the job. Because he enforced the penalties - we knew he would. I think we probably went 5 or 6 thousand over the 85,000 and he took it out of us.

But he gave you the chance.

Oh, yeah. That’s all we cared about. What difference did it make? So, after all this, he gets me down there - because by then I guess he knew I could write - and he says, »I want you to write this - this is going to be a big fad - the motorcycle picture.« And I said, »I totally agree with you about that, Roger.« And he says, »And here’s what you’ll get paid.« I said, »Roger, you know we’re very good friends by now and we love one another and I may hate the pictures you make but I’m in them, and if I wasn’t in them I couldn’t collect unemployment. I owe you this. But, Roger, I’ve worked for scale for you all these years and I’m not going to start as a writer that way. You have to give me a few hundred bucks above scale to write this picture for you.« He said, »I’m not doing it.« I couldn’t believe it. I said, »You’re not doing it. Well, then I’m not writing it.« And I didn’t write the picture. Now along comes The trip...

Roger was one of those odd people like me who experienced LSD, in a clinical situation. He wants to make a serious picture. He calls me in and he says, »Look, this is a subject that I want to do right, and I want you to write a good movie on this subject. And I’ll give you $200 over scale.« »All right.« Now I wrote this picture and in the middle of it I got my divorce. ‘Cause I was out changing the brake drums on my lawn with John Hackett, which was a savings of about $35. I give you these numbers so you know the scale I’m living on, with a family inside. It’s a tough job. You gotta go downtown to get a tool, and I couldn’t do anything. While we were doing that brake-drum job on the lawn, I got this job writing The Trip.. And I got a job acting in a picture with Cameron Mitchell which Bruce Dern’s business manager did on his credit card - I can’t think of the name of it right now. So, from an unemployed actor on my lawn, I got two jobs, which is why in The Shining. [1980] I’m in there with a wife and a child - and you know, I’m writing... And The Trip. is about a guy getting a divorce.

Did he shoot your script of The Trip?

Well, about half of it. Of course, he likes [Bruce] Dern so I didn’t get the part I wrote for myself in the picture. But I wrote a really good script.

And Roger goes ahead and shoots it. The first guy who read my script of The Trip. was a painter I knew up in Laurel Canyon. I said, »Here, read this for me, Tom, and see what you think.« I had just finished it. He read the script - kind of a phlegmatic guy. He got such a strong contact high off the script that he fell off the back porch into the bushes. I thought, »Well, it’s got a little something.« I’ll never forget it. So now they shoot the picture and, you know, I had a very open ending on it. And crazy [James H.] Nicholson and [Samuel Z.] Arkoff, in the company that Roger created - American International Pictures.

AIP - he created them. They put this wild optical on the end - where the last image shatters like a mirror - cidn’t even tell Roger (to give it a negative spin). I loved dealing with the nuts and bolts - pure, down to the bone. There was something about having to solve a problem, right or wrong, immediately. You didn’t think - »maybe I should think about« - you came up with it.

Seat-of-the-pants picture making.

Totally. That’s why Marty [Scorsese] and I worked so well together. »Let’s do it.« He’s not that stripped to the bone, obviously, but if you got the syntax, you know, you don’t have to talk too much.

How did Head. [1968] happen?

Well, Head. comes from [Bob] Rafelson and I meeting, talking.

It was after The Monkees. were a hit.

Monkees are a hit. Like everybody, I think, »What’s with The Monkees? It’s bullshit I don’t care about.« And I knew Rafelson, didn’t know Bert [Schneider]. We talked at the beach - about all that stuff serious cinephiles talked about. And we noticed we had a kind of similar outlook, ‘cause I always said, »Look, I don’t care about all this bullshit. I can write any movie that you want on any subject and I can do it in three weeks or less, I don’t care what you say.« This was like a bullshit coffeehouse boast. So I’m having this discussion with Rafelson one day out on the beach in Malibu and he says, words to the effect: »Well, look, do you really think you’re that red hot?« »Well, yeah.« You know, that kind of discussion - I’d be embarrassed to do it today. He says, »Really? Well, we’ve got a deal to write a movie for The Monkees. Why don’t you write a movie for The Monkees?« I said, »For The Monkees? I’m into Stan Brakhage and these people. We’re out there.« (In fact, I was working on something very theoretical myself: I lost the script, but it was called Suggestions for the Knoxville Bear.)

So when he says this to me, I said, »Monkees? I’ll be honest with you, I like them, they’re nice, but I’m a serious person.« He says, »Well, you claimed this and that...« Now Don Devlin and I used to get jobs where we had to make up a story overnight. We’d say, »Here’s what we’re gonna do for you,« and then we’d go home and try and remember what we said. Don and I wrote one of the first assassination pictures for Lippert and God, I almost killed myself. I crawled out of the dailies the first day and never went back, I was so offended. Devlin thought it was hysterical I wouldn’t go back to dailies.

What picture was that?

Thunder Island .- something like that. Why I walked out was I wrote this very complicated, 25-page parallel action sequence at the end with the assassination. People think about low-budget films today, it’s different. These movies, people didn’t even try to make them good. It wasn’t the point. But I wasn’t prepared for this. Somebody up in the church steeple and somebody in the confessional and the dictator out riding on the beach - I had a lot going on in this sequence. First day’s dailies, I’m sitting there, you know, I’m not looking for great movie-making here. And Gene Nelson’s in the picture and they reduce this entire action-sequence down to: he tripped over a branch. Not even a particularly good shot of a guy tripping over a branch. I sink to the bottom of my chair, roll to the ground and crawl out of dailies and never returned. So now, overnight - I think, »Okay, this’ll be a perfect movie, this movie for The Monkees.«

I sort of had the idea. And I go in to Bert, whom I didn’t know yet. This is another one of my favorite interviews. Bert says, »Well, what’s the idea, Jack?« I said, »Well, I got two ideas. One of them is what I’m actually working on as Serious Jack-the-Writer, which I can guarantee you almost unequivocally, no matter how hot The Monkees are, this will not make a nickel.« It’s like a joke interview. And I said, »And, I got another picture that I guarantee, though it’ll be a hard trick to pull, this will do the same thing A Hard Day’s Night. [1964] did for the Beatles cause it’ll be a really good exploitation movie.« And I’m sitting there ready to tell it to him and Bert looks at me and says, »I want the picture that can’t make a nickel.« Now, I’m just like you, I’m blinking. I’m thinking - I don’t even know what the fuck to say. I’m thinking, »Is he kidding?« And I’m looking at him and he says, »No, I want that, what is it?« And I now tell him. You know, in the underground, there are a lot of things about film loops, which is what Head. is.

I said, »Well, I’m trying to write a picture which doesn’t have a story linearly, but has a story by image and configuration.« Like classic imagery and classic configuration. I could do that. I could do that easily for The Monkees... I’m so astounded by the interview. I heard the Monkees already want to break up. And Bert, he don’t think anybody can write a movie that won’t be successful - The Monkees are too hot. I said, »It’ll be good, too.« So Bob and I wrote a film-loop story about the suicide of a group; and I got a lot of material from them. I said, »It’ll be good, too.« I just gave the idea - Bob didn’t even know what Bert picked or whatever. And in between times, Bert says, »Come on down on this, because it’s your idea and you’ll be the co-producer.« Things went well..

Right around that time. I didn’t know Bert well enough not to be succinct. »Look, here’s what Easy Rider is: I know this like the back of my hand. When a genre is taken up a notch - this, because of the level of its content - will be like what Stagecoach. [1939] was to the original western. Just by the fact it is better. Whatever else it is, you’re buying a motorcycle picture.« Fonda had been in

Wild Angels.. Made 8 million. Dennis [Hopper] had been in one. I’d even been in one - Hells Angels on Wheels. [1967]. And that had done 4 or 5 million. And these movies were made for 100, 200 thousand dollars. The guy who put up the money kept every nickel, so this guy made a huge amount of money. So I said to Bert, »Look, there’s no way you can lose at these figures. Plus, I think it’ll be big.« And that’s all I gave him. Now, later on; »They’re crazy, go down, play the part.« That’s how that happened. And after that, I knew exactly what to do - because I had those twelve years to think about it - exactly what to do.

When you saw the audience at Cannes...

Yeah. The audience was kind of weird and interesting. From the minute my character came on that screen, that entire, very cold audience, exploded. It was like being in the 42nd Street Theater..

I thought, »Jesus Christ, I gotta rethink my plan here.« I want to direct a picture, but in order for me to think about directing, I had to like bury certain acting aspirations. I felt I had to concentrate on directing and not split the focus or I wouldn’t get to do it really.

Then you decided to focus on acting.

Yeah. Part of my thinking was, »Well, I can still direct because I won’t have to get the acting job so much.« If I act, my aesthetic group - the post-New Wave generation of movie makers - instead of me making one picture every two years, we’ll as a group make two or three. That wasn’t the only reason, but hey, I’m a movie star, I had to explore it. I thought I knew what to do, and as it turned out, at that point I’m not a hick. You were there. For instance, look at Five Easy Pieces.. When I did Easy Rider., the audience thought that’s who I am - the big audience didn’t know me. So they think of me as a Southern lawyer-type, a Southern hick, weird lawyer and this and that - and what is Five Easy Pieces.? It’s a guy who starts off in disguise as a hick oil worker, and in the middle of the picture turns out to be an intellectual concert pianist. What could be more vehicular than that?

Didn’t Bob write that for you?

Bob and Carole Eastman wrote it.

Didn’t she write it for you?

Oh, absolutely. I knew the character - her brother-in-law - that it was based on. And we had a long relationship.

You and Carole?

Yeah. She wrote The Shooting.. That was her first script. She wrote a couple of interesting pictures after that. All the Frenchies want to use her. And dear friend. The Eastmans are my Glass Family [from Salinger]. She was in the acting class at Jeff’s. In fact, 5 or 6 screenwriters came out of that class.

Was there one moment when you had decided you wanted to write?

Jeff was the best at improvisational teacher of all time. He had a few very strict rules. No plot, no »fuck,« and you can’t say, »That’s ridiculous.«

Why?

Because it ends the discussion, as »fuck« ends any conversation. Once you say »fuck« you can’t drop back. You know, with The Departed., a Scorsese picture, the Ratings count the »fucks« well, there’s no way you can do a Martin Scorsese picture and stay under the limit for »fucks.« You can’t do it. That’s why we broke through a little bit in this period we’re talking about with Easy Rider.. We did a lot of law work at BBS, you may or may not know.

I didn’t realize that - law work?

Well, we went to the Supreme Court about these things. Carnal Knowledge., that was part of the thing, Five Easy Pieces., and Mike Nichols - he’s the guy I couldn’t get an interview with - for The Graduate..

Carnal Knowledg.e came to be. I’m at the end of a love affair, I’ve done Easy Rider.. I think it’s good, but I’m not thinking it’s that! Who would? Nobody. When it happens, I knew it’d be good - I’m not thinking this is gonna involve me this way. So I’m now down on a trip through the dope fields of Mexico, kind of as a reminiscence on behalf of a friend of mine, just a trip down into Mexico, way down. On the way, we go through Guaymas. We’re having a tremendous amount of great adventures and fun. Comes that moment in Mexico where you say, »I gotta get back.« So we now turn around, we go back. We now arrive in Guaymas, and there’s lights strung up, there’s music - we’re in the dark - two guys with beards wandering out like Sierra Madre.

Who’s with you?

Red Dog - I can’t say. We went through Guaymas, a derelict town on the way, and here’s all these cars. So we ease up on one end of the bar, and then we find out Nichols is down there - the guy I couldn’t get an interview with - shooting Catch 22.. They moved in there. I knew Buck Henry - Buck comes in. We’re at the bar, hoisting one up, looking around at the movie yucksters. Buck comes over and we’re talking like this and [Art] Garfunkel came over - that’s when I met him - we’re just drinking at the bar, making a movie - that’s interesting, and so forth. Now Mike comes in, he looks at me at the bar - the guy who is the king of the movie business, I couldn’t get no interview with. And he looks at me and he looks at Buck, and he says, »You know this actor right here?« Buck says, »Yeah, this is Jack Nicholson.« He says, »Jack Nicholson! I just cast this whole picture of actors this age for Catch 22. and you know this guy and you didn’t tell me...«

Because he had seen an early cut of Easy Rider. - this is like my first response to the picture. I’d been down in the weeds. So I’m thinking, »What the hell is he talking about? My last experience is: this is Mike Nichols and I can’t get an interview.« So now, »what’s wrong with you, Buck?« I wasn’t that happy about the discussion, quite frankly, I’m still more on the side of »couldn’t get an interview.« »Well, people are gonna like Easy Rider, and off we go.« Well, his next picture was Carnal Knowledge. - And I’m the next guy with the biggest director in the country, and I know that’s a move you gotta make.

I had plenty of plans - I never didn’t think of myself as a smart guy. Nothing went the way I planned it in this period - it all went better - in every way, including I wouldn’t have to do those twelve years again - the sweating - but now that I was past ‘em, I love knowing what I learned in those twelve years, because not many people get there knowing that. That’s why I said it worked better - I wouldn’t have planned on it.

So when was the moment you decided you wanted to write?

With Monty [Hellman]. And Devlin got me writing - my dear departed Don Devlin. You know, Fred Roos was a big supporter in the early days and part of our crowd. He said, »Look, Lippert wants an action picture.« I forget if I’d written the other script with Monty first or not. Same period. The Monty script I wrote we never shot. This was a spec thing he wanted to direct about an actor. Years later Fred got me an offer for that goddamned script, the one I wrote for Monty. But I had lost my copy. With Devlin, it was, »Hey, we’ll make a few bucks maybe« - we got the job, we wrote the script. That’s the way we did it. Orson [Welles] said, »The actor who writes is the ideal personality for film.« I used to listen to everything he ever said like it was the gospel.

Orson wanted to do that picture [Midnight Plus One.] with you and [Robt.] Mitchum.

Yeah. It would’ve been good. It was Orson’s version of Apocalypse Now actually.

He got discouraged.

We said yes to everything.

He got discouraged because Mitchum said no.

Did Mitchum say that? At that point he could have done without Mitchum.

How did you like working with James L. Brooks.

Jim’s ability to rewrite on his feet is amazing. There’s a saying about acting: »The actors need to fail.« When an actor reads a scene, if he doesn’t like it, it’s really because he fears it, or he hasn’t really tried to work out the scene. So, normally, my process is: Try to do the scene first, and then work it from there, and that’s the best way to do it. Classically taught that way. With Jim Brooks I worked differently. Because if I tell him there’s something about a scene that I don’t like - even if it’s not a particularly big thing - he goes away after listening to me, and like clockwork, ten to fifteen minutes later, comes back with a better scene. Automatic. Jim’s just phenomenal:[ snaps fingers] better scene! It stimulates him in some way.

What was Scorsese like to work with?

Martin, I felt through the length of this production, very much likes to work in his own world and work alone. That’s the way that artist likes to work - and that’s fine by me. I don’t particularly push contact, but always make it known I’m available, or not. I can’t think of many »or nots« but - if they want you to do something and it’s geographically impossible, that’s »or not.«

He sends his best. I spoke to Roger Corman today.

My Man.

He sounds exactly the same on the phone as he did forty years ago.

Integrity will age you well. He’s one of those people, you know, I feel like I see him all the time, but haven’t seen him.

He’s still making pictures.

Of course. He’s got it together, as they say.

Would you say those Westerns with Monty were the first pictures you really were proud of?

There were a few things before that certainly had pieces I could say I was proud of.